Introduction

I grew up playing poker with my friends and family. Ever since I was little, I have been interested in the math behind poker games and board games. Because of the complexity of the game rules, it is not often intuitive to figure out the optimal strategy of the game or even just write down its objective function. However, the simulation approach helps us understand the game. The better you understand probability distribution of the outcomes from your move, the better strategy you can make, thus the higher chance of winning.

When playing a poker game, players usually take turns shuffling the deck of cards. This seemly small feat, determines what hand you will get. But many people do not pay attention to the randomization of the cards. Is your usual shuffling method good enough? Does one strategy outperform the others? Do you shuffle too few or too many times? In this post, I am going to simulate different poker shuffle strategies and answer the questions above.

Suppose we label the 52 cards in a standard deck as 1, 2, ..., 52 and start with a deck (or state) $X_0$ which is sorted from 1 to 52. Then we simulate the following different shuffling processes iteratively from $X_{t-1}$ to $X_{t}$.

Strategies

Bottom-up Shuffle

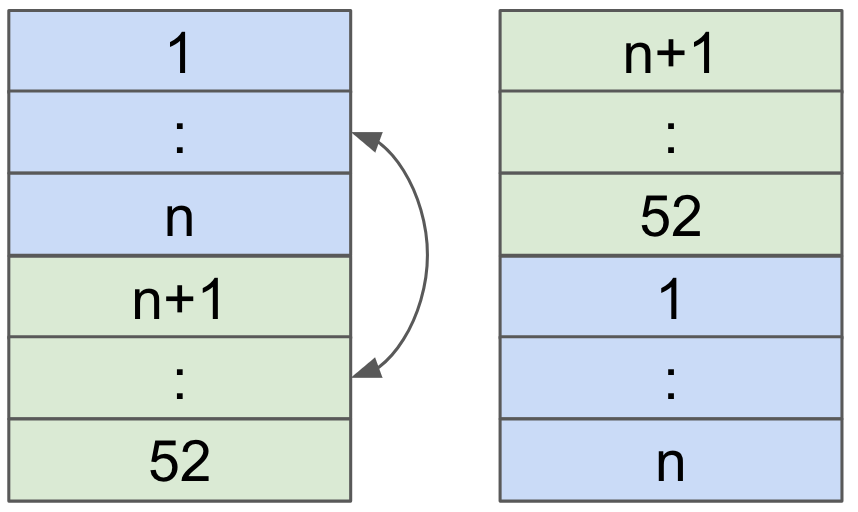

This is a very popular strategy in China because it is quick and easy to execute. Even if you have never seen this, it is not hard to imagine how it works from the name. Basically, the player casually holds the top n numbers of cards in one hand and move the bottom 52-n cards on top with the other hand, where n is supposed to change after each shuffle but targeting 1 << n << 52. This method is simple, though I rarely see people use it in America.

There are other strategies similar to that. For example, people, including myself, like to perform full-deck bottom-up shuffle (where you hold the initial n number of cards from the bottom half of the deck and continue to shuffle it bottom-up, without releasing the initial last few cards, making n smaller and smaller). However, this strategy is hard to standardize, so I'm not going to include it here.

def bottom_up(self, deck):

n = len(deck)

n_cards = np.random.randint(n * 0.25, n * 0.75) # hardcoded the middle 50%

shuffled = list(deck[n_cards:]) + list(deck[:n_cards])

Riffle Shuffle

This is the most popular hand shuffle strategy in the poker world. Per my observation, almost every poker dealer in a casino uses this strategy. The shuffling process looks like this, 1) the player splits the deck into two roughly equal parts, holding one half in each hand; 2) release the cards from both hands simultaneously, and stack the cards alternatively from each side. However, this strategy can easily be performed differently by different people. Here I break it into two main differences.

Complete Riffle Shuffle

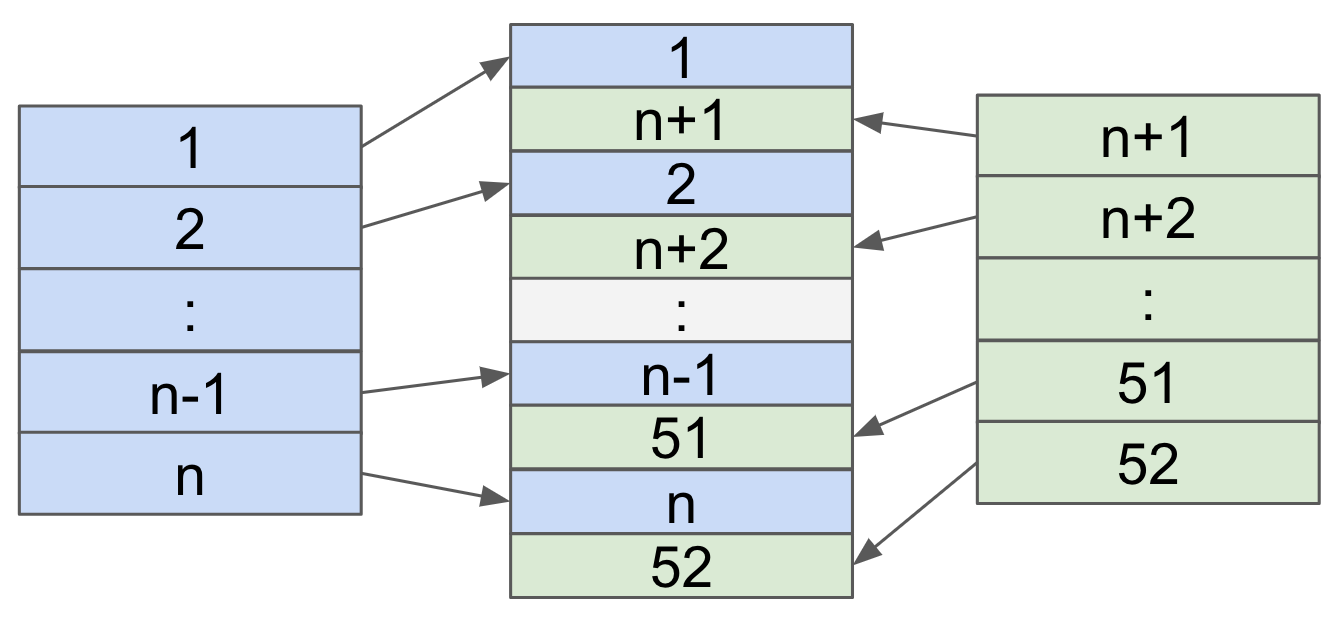

This strategy is when the two halves of the cards alternatively stack on top of each other one by one. This can usually be seen in performances of professional dealers or cardistry. The main reason people would do so is that this strategy can minimize the friction among the cards after the mix, which allows the players to smoothly execute a following move, eg: a bridge, to recover the deck into a uniform shape. One needs lots of practice to acquire such skill, however, it looks really cool!

The implementation of this is simple. Given a sorted list, break it into two halves. Going through each list, inserting a element from a list followed by one from the other list, and continuing on with the next elements. Something to be careful about, is that we shouldn't always start with the 1st insert from the same list (i.e. don't always release the card from the same hand first every time), because if you do so, the first and the last element won't be shuffled (i.e. the top and bottom cards are always the same regardless of number of shuffles).

def complete_riffle(self, deck):

n = len(deck)

x_l, x_r = deck[:n/2], deck[n/2:]

shuffled = [None] * n

if np.random.uniform() > 0.5:

shuffled[::2], shuffled[1::2] = x_l, x_r

else:

shuffled[::2], shuffled[1::2] = x_r, x_l

return shuffled

Random Riffle Shuffle

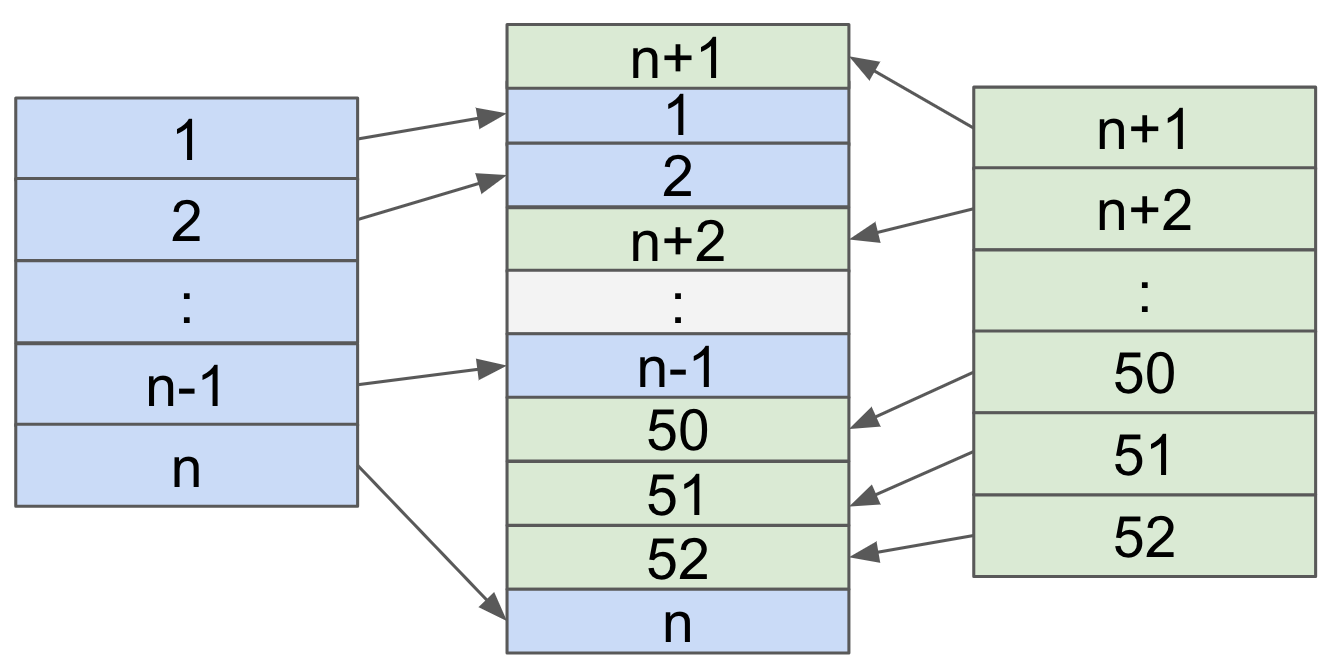

On the other hand, if you are as clumsy as I am, you may not be able to perform a Complete Riffle Shuffle consistently, then you would end up doing what I call Random Riffle Shuffle. This is when two halves of the cards stack on top of each other but not perfectly one card after the other. This seems to be more common among people who perform a riffle shuffle. This method causes more friction among the cards so it is harder to perform a following trick compared to Complete Riffle.

One can implement this strategy on top of Complete Riffle Shuffle but it is kind of counter-intuitive. A workaround approach can be something like this. Simulate 52 independent Bernoulli trials with probability, p=0.5 (to maximize randomness), to be 0 or 1. Suppose there are n zeros and 52-n ones. We take the top n cards from deck $X_1$ and sequentially put them in the positions of the zeros and the remaining 52-n cards are sequentially put in the positions of ones.

def _gen_shuffle_index(n, p=0.5):

index_0 = []

index_1 = []

for i in enumerate(np.random.binomial(1, p, size=n), 1):

index_0.append(i[0]) if i[1] == 0 else index_1.append(i[0])

return index_0, index_1

def random_riffle(self, deck):

n = len(deck)

index_0, index_1 = self._gen_shuffle_index(n)

shuffled_tuple = zip(index_0, deck[:len(index_0)]) + zip(index_1, deck[len(index_0):])

shuffled = [i[1] for i in sorted(shuffled_tuple)]

return shuffled

Simulation and Evaluation

We always start with a sorted deck $X_0$ and repeat the shuffling process $K$ times. Thus at each time $t$ we record a population of $K$ decks: $$\{ X_t^k: k = 1, 2, ..., K \}$$

For each card position $i = 1, 2,..., 52$, we calculate the histogram (marginal distribution) of the $K$ cards at position $i$ in the $K$ decks. Denote it by $H_{t,i}$ and normalize it to 1. This histogram has 52 bins, and we can choose a large $K$ (I use $K$ = 10,000) in the simulation. Then we compare this 52-bin histogram to a discrete uniform distribution, $U$, by L1-norm and average them over the 52 positions as a measure of randomness at time $t$. $$err(t) = \frac{1}{52}\sum_{i=1}^{52}|| H_{t,i} - U ||_{L1} $$

Result

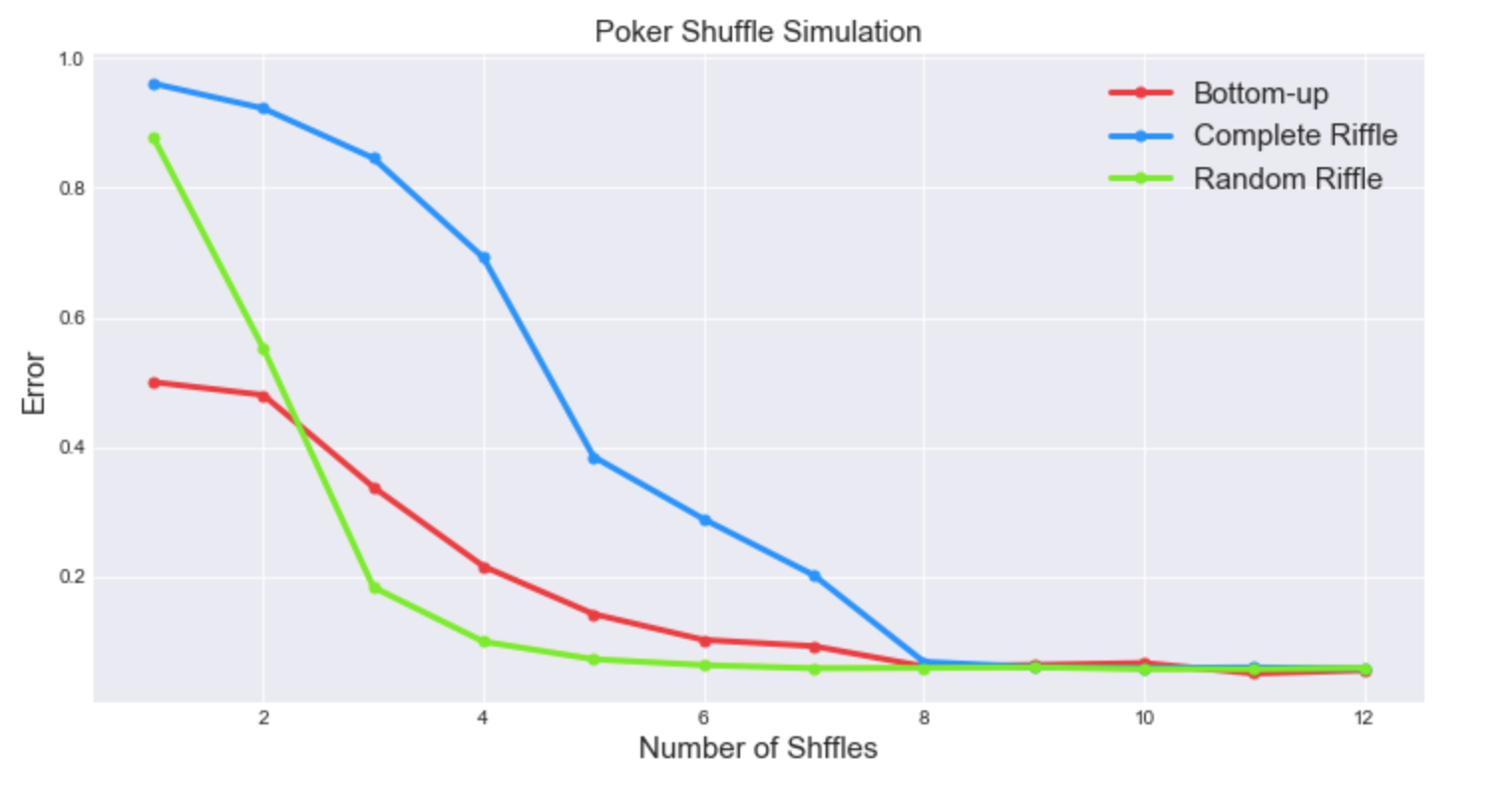

Below is the simulation result with $K$ = 10,000. (code & notebook)

The result may look surprising because Complete Riffle converges slower than Random Riffle and even the naive shuffle method of Bottom-up. If you think about it, this is actually self-explanatory.

Let's look at an extreme case, say we only shuffle once for each simulation process.

By definition, Complete Riffle only has 2 possible outcomes: your left hand releases the bottom card first and your right hand releases the bottom card first. Then after a large number of simulations, each position $i$ of the deck can only have two outcomes, which is far more than random, i.e. the distribution of the cards is very different than a uniform distribution.

On the other hand, Random Riffle has more randomness by definition because in each shuffle 1) the number of cards in the left hand can be different than right hand, and 2) the cards both sides don't need to stack on each other one by one which causes way more different ways of sorting after the shuffle. However, both riffle strategies are stacking the cards in sequential order, so the randomness (defined) at first won't be too large, but the later will drop quicker because it creates more randomness in each shuffle. (Remember we are looking at the distribution of the cards after a large number of simulations, not comparing the one-time outcome by chance to the original deck!)

For Bottom-up strategy, I hardcoded the number of cards being on top so that it will within interquartile range (middle 50%) because I think this would be in line with what most people do.

If we only shuffle once, after a large number of simulations, each position will have 26 different possible outcomes, so the error drops to 50% at first shuffle. However, the convergence speed is not faster than Random Riffle.

Let's digest the above explanation by answering this question: how easy is it to guess the bottom card after the first shuffle respectively using these three different shuffle methods. It is easy to guess if the method is Complete Riffle or Random Riffle. It would be either 1 or 27, though it is harder to guess the middle part of the cards for Random Riffle. If the method is Bottom-up, the bottom card can be anything between 13 and 39, the middle 26 cards, so it is hard to guess even after one shuffle.

Final finding is that, no matter what strategy we use, after the 8th shuffle, the card is pretty random, which means, on average, the card in each position should have equal chance to be any card in the deck. No need to shuffle more than 8 times!

Ending

Understanding the above may not help you increase your winning rate in a casino, but it is good to know that the way those pro dealers shuffling the cards does not perform better in terms of creating randomness. Some shuffle methods look cool but take longer to finish. I would just stick with a quick simple one and use the time to shuffle more times. Remember, if you are not doing something crazy, we only need to shuffle the deck 8 times! Enjoy playing cards!

Leave your comments below.